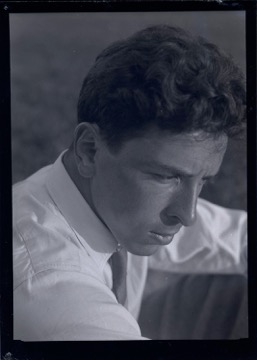

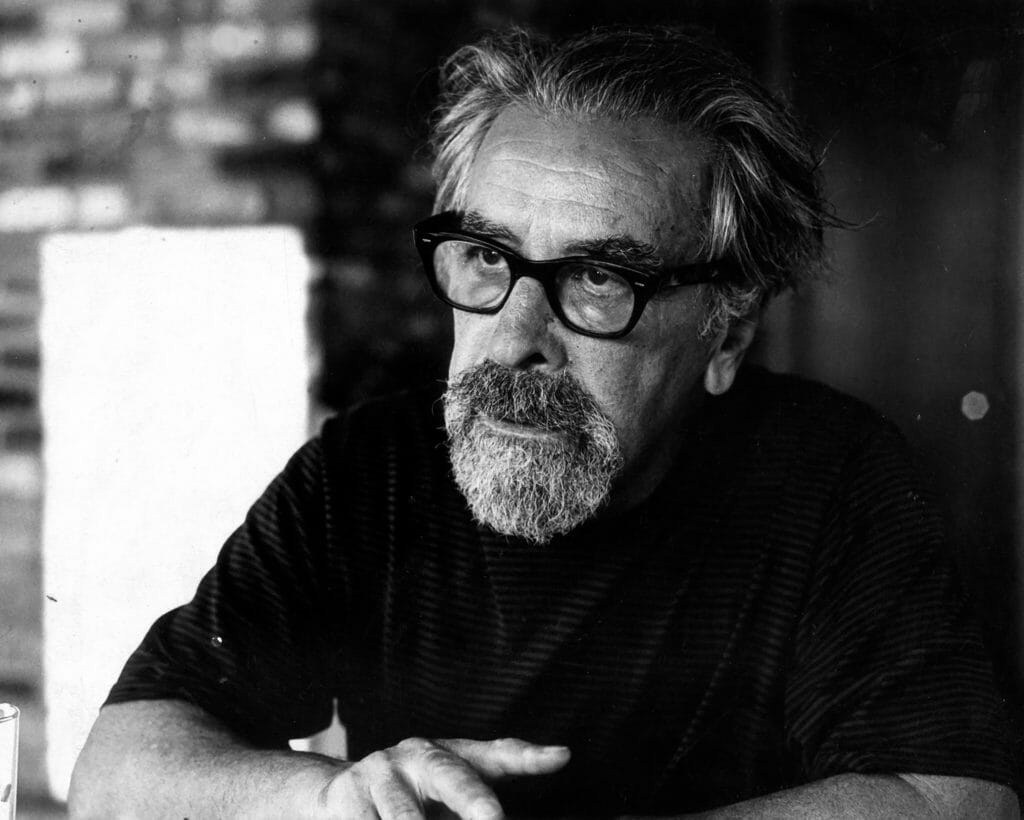

LEO HURWITZ

A Pioneer In The Beginnings Of America’s Documentary Film Part 3

A Radical Filmmaker In The Making

“Leo Hurwitz’s task in life: creating and practicing the documentary film tied intrinsically to the quest for human freedom, liberation, equality, and truth.” Tom Hurwitz, Leo’s son.

In 1926, Leo went to Harvard. This was quite an achievement for the Jewish son of working-class immigrants. Yet remarkably in line with the family’s intrinsic belief in, equality. Leo’s unusual intelligence and literary interests didn’t escape his sister Eleanor’s fiancé, Paul Anderson, in his own last year at Harvard. Leo had inherited his father, Solomon’s, passion for ideas and his mother, Eva’s, creativity. At New Utrecht High School, he was editor-in-chief of the literary magazine, The Comet. Leo was also president of the dramatic society. Observing and knowing Leo, Paul suggested that he sit for the Harvard Club scholarship exam. He received the highest score and won. Upon high school graduation, Leo was off to Cambridge. And, on his way, along a slightly circuitous path, to becoming a radical filmmaker.

Science Versus Art At Harvard

Leo didn’t start out at Harvard intending to be a filmmaker. In fact, film wasn’t remotely in his mind. His decision to become a documentary filmmaker came slowly and much later. Leo went to Harvard to become a medical doctor. Eva, his mother, a midwife and medical practitioner herself, was likely a quiet inspiration. Yet, Eva was also creative. There were two pulls in the Hurwitz family, intellectual pursuits and creative ones. This was true of my own mother, Charlotte, the first Hurwitz grandchild, Leo’s oldest brother Bill’s daughter. She herself couldn’t decide between becoming a modern dancer or a doctor. Medicine won out and she became a psychiatrist. But, dance, sculpture, and poetry were never far away.

The Hurwitz family had creative gifts. Older sisters Elizabeth and Sophia were dancers and Eleanor a sculptress. Writing is a talent of many in the extended Hurwitz family. And, Leo’s mother could sew and create any desired garment. Leo spent numerous hours at Eva’s feet, watching – as she cut fabric and pieced it together into dresses for his sisters:

Watching Mother Sew

“I used to hang around while Mother cut patterns and pinned them on Marie and Elizabeth. Played an important role in my sense of creativity. I’d watch Mother transforming the idea of a dress into paper cutouts, which were pinned together, fitted, reshaped, made into another pattern, and then cut on the floor or on a table. The cloth was chosen for the way it would fall or the color. This fascinated me – this making of things. One day it hit me that I’m a cutter, an editor – I put things together in another way.” (Told to Ellen Hawley, Pete’s daughter, in her 1985 interview)

With dressmakers, dancers, sculptresses, psychoanalysts, and midwives in the Hurwitz family, both art and science had powerful influences. Yet, science wasn’t really Leo’s inclination. Particularly when it came to facts that weren’t linked to any deeper meaning. He took advanced inorganic chemistry in his sophomore year and did well on the experiments. But he had no memory for the answers to test questions. He thought: “If this is the stuff of medicine, isolated logical facts, then I don’t have it for medicine … I’d sat in on some art classes. I had it in my mind to go into film.” (Hawley, 1985)

Graduating From Harvard & Teaching Himself Film

In 1930, Leo graduated from Harvard in philosophy, as the top student in the department, studying under Alfred North Whitehead. He expected to get a fellowship to continue his studies in Europe. It was a scholarship that was uniformly given to the student who graduated in his position. The fellowship wasn’t awarded the year Leo graduated, which was unprecedented. Leo’s tutor, Robin Field, is certain that the reason was anti-Semitism. Leo did, however, graduate Summa Cum Laude with Phi Beta Kappa honors in philosophy and psychology. What to do next to begin his career in film?

It wasn’t an easy road. In the 1930”s, there was no one teaching film except in the Soviet Union. The apprenticeship system was the only way to learn filmmaking in the United States. Leo wanted to study with Charlie Chaplin: “I had admired him as a child then realized he was a great artist. I wrote offering to take any job at all just to hang around.” (Hawley, 1985) Chaplin didn’t respond. Paramount Pictures on Long Island didn’t respond either.

Leo bought himself a movie camera and decided to teach himself how to make films. He’d graduated from Harvard during The Great Depression, a troubling time for many people. All around him were previously employed, homeless men, building shantytowns in Central Park. This human suffering was what Leo wanted to speak about through his film images. He’d learned early, in his first experience of movie-going as a child, what kind of films he wanted to make. And also the genre he did not want to perpetuate.

Childhood Influences: The Art of a Good Film

Tom Hurwitz, Leo’s son and also a documentary filmmaker, says this about Leo’s main filmmaking objective: “Away from the world of seduction, that was Leo’s essential task in life.” The problems of real people, problems too often pushed aside and ignored, those were the ones Leo chose as his subjects. His dislike of seduction started very early, both in his family’s focus on the reality of social concerns and in his own first experience of film.

Leo was born in 1909, close to the origins of filmmaking and film production. He saw his first movie with sisters Sophia and Eleanor as a child of about four or five. Leo remembered well his original movie-going experience:

“We were in a darkened theater and here were these immense images … they looked real … shadows with real features and they were monumental. I was little and that was huge. It had the extraordinary vivid experience of a dream.” Yet, with this dreamlike feeling, there was something not right. He felt he’d been ‘hit over the head:’

“I knew, then, that something was wrong with the movies if I felt this way. To come from the movie to the real world required a shock of transition. That shouldn’t be … when I saw a film where I could make a transition to the real world without shock and disruption; I knew I’d seen something extraordinary. If I felt hit over the head, I knew I’d seen something that may have been remarkably seductive and remarkably hypnotic, but it was not a good film. It was out of the world of seduction.” (Tom Hurwitz’s 2009 UCLA lectures)

The Worker’s Film and Photo League

There was nothing seductive or hypnotic about The Great Depression. Seeing human pain all around him led Leo to look for something to do about it. He found both the Communist Party and The Worker’s Film and Photo League. In the early 1930s, there was a huge growth in the Worker’s Arts Movement stimulated by a directive from the Soviet Union that saw art as a weapon in the class struggle. But the Worker’s Film and Photo League didn’t come solely from this directive. It was part of an expansion of left arts groups, agitprop, nationwide left-wing news coverage, and experimentation in form and content. By people with growing political awareness and no place for their creativity:

“In 1931, I heard about the Worker’s Film and Photo League. I read of it in the Worker. It had been a part of the Workers’ International Relief, which helped strikers and dealt with cultural matters … The League made photos and newsreels of events that weren’t covered by regular papers and newsreels. In ’31, the Hunger March to Albany, in ’32 Bonus Marchers driven from their encampment by Douglas MacArthur and their shanties burned. Scottsboro case. It was a very valuable organization. I had some experience shooting by then … it was a place for me to work in my own medium and in connection with an aim – to communicate what was happening to others, to extract meaning.” (Tom Hurwitz’s 2009 UCLA lectures)

Communicating What Is Happening To Others

These were important objectives for all the Worker’s Film And Photo League’s members during the 1930s. Including Leo Hurwitz, Tom Brandon, Lionel Berman, Irving Lerner, Jay Leyda, Sidney Meyers, David Platt, Leo Seltzer, and Ralph Steiner. These men were newcomers to the cinema, predominantly Jewish, unemployed, politically conscious. They set about creating America’s documentary film.

In 1930, the United States had no documentary film. At the end of the 1930s, these men had created the documentary film as an art form that gave people information about their worlds. Leo and others, most notably with Paul Strand, pushed the development of the social documentary as far as it went by 1942. According to Leo’s son, Tom, no one fought for the creation of the social documentary form more strongly than Leo Hurwitz.

Newsreel To Documentary With An Emotional Center

The Worker’s Film And Photo League (WFPL) primarily filmed newsreels of strikes, demonstrations, hunger marches on Washington, and the like. These films were agitprop and badly made. The members of WFPL, men who were strong individualists with a passion for their own ideas and a drive to create better films, began to watch films coming out of Russia.

Leo’s interest in Russian films and his tie to the Communist Party led the FBI and The House Un-American Activities Committee to follow Leo closely. Yet, there was never any evidence of a Soviet directive to use his films as propaganda. His only goal was to learn from the quality of Russian films. Inspired by watching his mother’s cutting of fabric sewn into beautiful garments, Leo was interested in the power of editing:

“You have to do more than show unemployment [for example]; you have to get to the why of it and the experiences that don’t show in a newsreel photo. We needed what at that time we called a “shock troop”… others agreed to move this way. We started some classes on technique – how you shoot, how you break down a scene … there was opposition … I argued … [that] you work towards the accumulation of skills and art … I said this not a competition, but to discover the experiences that are happening and find a film form for them … I didn’t win the argument.” (Tom Hurwitz’s 2009 UCLA lectures)

From WFPL To Forming Nykino

In 1935, Leo, Ralph Steiner, and Sidney Meyers left WFPL to form Nykino with Leo at its head. Paul Strand and Elia Kazan were also a part of Nykino. Leo formed a partnership with Strand, already known as a still photographer. That same year, the two were commissioned by Pare Lorentz to write a script about the conditions in rural America on the prairies. They also did the cinematography. This film was called “The Plow That Broke The Plains.”

Lorentz ultimately threw out the script. But Leo and Strand’s photography remained, as well as an idea for a new form of documentary. Leo Hurwitz and Paul Strand moved away from a simple narrative structure to a documentary that would tell a story with an emotional center.

Leo’s Documentary Voice: The Structure Of Need

The core members of Nykino continued on to become Frontier Films (1936-1942). Here the real creation of the American documentary took place. Paul Strand was President and Leo Hurwitz and Ralph Steiner, the two VP’s:

“When I set up Frontier Film – most organizations established a connection to the Party (Communist Party), which provided guidance and help to raise money. We decided we were Communists but didn’t need any schoolteacher guidance. We discussed nothing artistic with (the Party’s) liaison. Around you was rigid thinking, but you could bust it open … there were tremendous developments in the arts – a revolution in film, theater – burgeoning creativity in the ’20s and early ’30s. The best films were Russian, both in exploring the form for poetry and drama in dealing with the world.” (Hawley, 1985)

This kind of poetic and dramatic form was what Leo was looking for. In 1937, he and Paul Strand edited the film Heart Of Spain, a film that recorded the early activities of Hitler’s Party in Spain in 1936. With this editing project, Leo and Strand began to develop their new structure. Leo called it ‘the structure of need.’ The film had to evoke an inner need in the audience. The ‘structure of need’ involved a film showing a series of needs, an obstacle to those needs being met, and then the resolution. Leo used the internal needs of his films to structure the film, as opposed to the more common way, which was to tell a story chronologically or as a series of conjunctive. No one in America had yet built a documentary film around an emotional idea.

Creating An Emotional Center

Creating an emotional center in the documentary film was Leo Hurwitz’s critical contribution. Through his new ‘structure of need,’ documentary film began to form an emotional link from the audience to the people on the screen. People suffering and persecuted and without social justice: “It could be us. What do we do about it?” The emotional pull to action that Leo’s films evoke is at the heart of empathy. We’ll see this emotional structure and the empathy it creates as I begin to discuss each of Leo’s films.

Empathy is also at the heart of psychoanalysis, a pursuit that Leo’s sisters, Rose and Marie, followed to Vienna. They were both teachers. Not so different from Leo’s desire to emotionally relate to his subjects, their goal was to learn more about how to help and understand the children they taught.

Acknowledgments

The bulk of the information in this piece is from Leo’s son, Tom’s, lectures on The Roots of A Radical Filmmaker, Feb. 22-23, 2009 at UCLA. The UCLA Center for Near Eastern Studies hosted an international conference exploring the impact of the film, radio, and television broadcasts of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Leo, age 51, recently blacklisted for 12 years, was chosen by Capitol Cities Television to direct the television coverage of the entire Eichmann trial. The rest of the material for this piece is from my cousin Ellen Hawley’s interview of Leo in 1985 while conducting interviews of the Hurwitz family siblings.