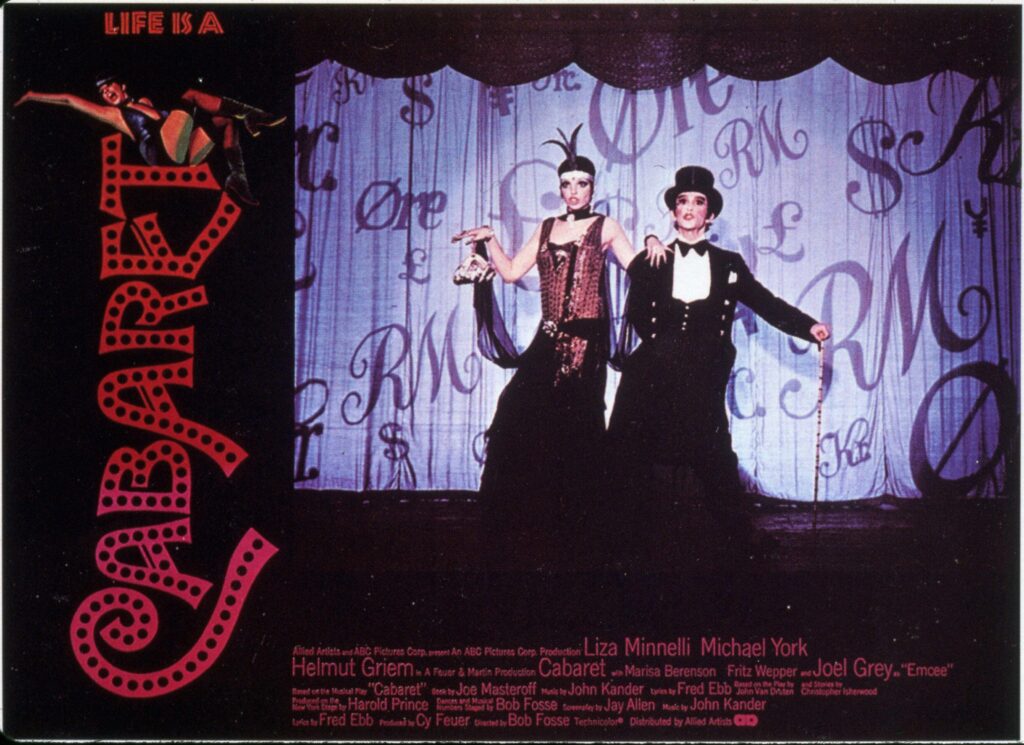

CABARET

How Quickly Freedom Disappears

It’s frightening how quickly freedoms can disappear. The question is: Why is it sometimes hard to see the complicated forces, in the outside world and living inside us, that want to deceive us if we aren’t aware. What blinds us can make us vulnerable. Cabaret is a powerful and disturbing illustration, plus a startling reminder, of the various ways these dangers lurk. Over Labor Day weekend in 2018, I saw a remarkable performance of Cabaret at the Celebration Theater at The Lex in Hollywood. I thought it was worth posting this piece again. Director Michael Matthews’ version of this well-known and loved musical crosses all conceivable boundaries; where anything goes. And, doesn’t.

If you’ve seen Cabaret, you know the play takes place in 1930’s Berlin, at the time Hitler was vying for power. A frightening time; especially in the ways that Hitler’s seductive promises veiled a thirst for power that would murder, provoke fear; destroy lives and hope. We see, in the 1930’s form of Hitler and the Nazis, the external forces working to undermine freedom. But, it’s just as important to understand the internal barriers that make it impossible to freely love someone that you actually do love.

Seductions

Entering the theater, scantily dressed women dancers are moving sensually on stage in suggestive poses. Male dancers join them with lewd bodily touches, stroking; forming twosomes and threesomes. The purpose is to seduce, to titillate. And, they do.

The Emcee jumps out onto the stage, leaping up on a ledge as close to the audience as he can get. I am in the front row. “Ladies and Gentleman! Welcome to our show.” His voice, harshly sinister, is not welcoming.

Brandishing a sharp, shiny, and detachable finger that comes on and off throughout the show, The Emcee puts it on now; and every time he has something he must say.

Leaning towards the audience, he points that finger at us, in a strangely foreboding way: “Let the show begin!” He turns with a flourish, flitting off the stage Puckish-like, leaving us, but only for the moment.

We are put on notice. His apparent welcome isn’t to be trusted. Having successfully seduced us into a show that isn’t, in its bones, the loose bodacious erotic fun it appears to be on the surface, he will show us what and who he is.

The Emcee

The Emcee is Everyman. A starkly intense, vulnerable, often manic, fractured demonstration of all the conflicting forces struggling for dominance in every human mind.

He is power. Fear. Weakness. Light. Darkness.

He is life. Death. Man. Woman. Nazi. Jew.

He’s invincible at times and he’s broken in the end, shattered by the forces of hate within him and in the world.

He announces and pronounces each and every thing that will and does occur in Cabaret:

We’re introduced to cabaret dancers and lonely people coming together: to an American writer and the beautiful Kit Kat Club’s performer Sally Bowles. To a German spinster and a widowed German Jew.

They each struggle with love and with their histories of disappointment. But, let us not forget. This is the time of Hitler’s entrance onto the world stage.

At first, we don’t see it coming. We’re well into our love stories when suddenly the seemingly friendly, sly man named Ernst sweeps again onto the stage.

Proudly, provocatively and authoritatively he enters the scene – sporting an armband with a loud red Swastika. On this note, Cabaret turns ominous.

There is horror – as the Emcee continues to take on and off his sharp pointed finger, with its lessening power to convince.

At the center of Cabaret’s erotic hedonism, the Emcee is the pivotal force around which the hidden, darker emotions of two tragic love stories unfold, interrupted, unable to go forward.

He narrates the untold parts of these stories; playing out, center stage, what the lovers cannot say. The cyclone of emotion brews and explodes around and inside them. Love cannot survive in the midst of fear or hate.

The German & The Jew

Schneider is a spinster. She runs a boarding house in the middle of Berlin. There the American writer, Cliff, ends up, befriended and “helped” on the train from Paris to Berlin by a German – the shifty and secretive Ernst.

Cliff’s is the other story.

For now, we see Schneider, taunted by her prostitute boarder, Kost, who makes her money on the comings and goings of one sailor after another. Kost doesn’t try to hide it and Schneider finds her behavior upsetting. But Schneider needs money too and sacrifices her morals.

Yet there’s something else. Kost’s constant pursuit of men confronts Schneider with her own hidden longings. And, then there’s Schulz. He lives in Schneider’s boarding house too.

A widowed Jew who owns a grocery, Schultz is as lonely as Schneider. Every day he brings her an offering of fruit from his store. He loves the fruit as much as he secretly loves Schneider.

Love’s Dangers

Schneider is shy of love; perhaps feels unlovable or at the very least that her time passed long ago. But, the kindly Schulz is quietly persistent. He courts her with his tasty gifts, until, one night, longing takes over. He knocks on her bedroom door, and she pulls him in.

For Schultz, it isn’t a one-night stand. He pursues Schneider with a waltz, gentle kisses, and a proposal of marriage. He’s shy too, knowing love can be lost. Yet, quietly and hopefully, they are in love – showing that love does not escape anyone if they are open.

But, a force beyond their control enters the boarding house and disrupts the happiness of their engagement celebration. That force is the Nazi Ernst, with his Swastika armband, who marches sweepingly in, not to celebrate – but to warn, coerce, and to enlist.

The lewdly free Cabaret dancers turn rigid. They now too sport Swastika bands and salute “Heil.” Their movements are bound by the Nazi goose-step, and they don’t deviate as they join ranks with Hitler’s crew.

Happiness has become subject to threats and doubt. A German cannot marry a Jew. Schneider runs away. The respectful Schultz lets her go. Their love destroyed by a dictator’s hate. Their love destroyed by Schneider’s fear.

The Dancer & The American

Schneider’s not the only one afraid to love. Sally Bowles, the Kit Kat Club star, has always been afraid. That’s why she flits from one man to another. That’s why The Emcee, acting as a pimp, supports her affairs.

Sally spots Cliff, the American, at the Cabaret club and telephones him at his table. He’ll be her newest conquest. They meet for a drink. She’s beautiful, vulnerable, needs someone – and Cliff is lonely in Berlin.

So, Sally ends up at Schneider’s boarding house too, living with the American writer, trying to escape her past. Problem is, she starts to love him. But, love is no simple thing for her.

Sally and Cliff’s love affair grows even more complicated when she tells him she’s pregnant and doesn’t know who the father is. It “could be” Cliff. He wants to make a family, thinking it might tame Sally. He loves her too.

When it becomes clear the Nazis are infiltrating Berlin, Cliff insists they move to America, to his hometown in Pennsylvania, to start their new life.

That kind of change terrifies Sally, already afraid of love. Without telling Cliff, she aborts the baby. He feels betrayed. He also feels the losses Sally can’t and won’t feel.

Sally would rather turn away and go back to the Cabaret than risk love; disappointing or abandoning her. She tells Cliff she isn’t made for love; never has been and never will.

Freedom Gone in Cabaret

Hitler’s infiltration of Berlin along with invasions of psychological fear is the undoing of all:

Schneider, the German, remains a spinster, a reflection not only of her fear of Nazi powers, but also her long-time belief that love isn’t in the cards for her.

Schultz, the Jew, is in denial. He’s a German. How could he be treated differently than other Germans? But, he lets go of Schneider. What choice does he have? He already knows loss.

Cliff, the American writer, is the only one that gets out of Berlin, having suffered loss too in his time there.

But, the fate of The Dancer and The Emcee are most emblematic of what can happen when destructive forces rob us of internal freedom to be and to love.

What We Have To Fight

In Sally’s final scene, we witness her falling apart before our eyes as she tries to sing and dance once again on stage at the Kit Kat Club. She’s no longer the effervescent, bawdy, titillating performer/seductress she once was.

Her song is strained, words barely escape her lips; they are forced last gasps of the life and love she could not choose.

Close to the tears, she cannot cry, Sally stumbles off stage in an almost attempt to run. She can’t; destroyed by the way she’s turned away from feeling anything; killing her baby, a symbol both of the future and of hope.

Hope is gone.

By the end of Cabaret, The Emcee too is a mere shell of his former daring, taunting, roguishly sinister self. As Everyman, he is torn apart by the contradictory pieces of himself – including Nazi and, in the end, Jew.

The Emcee, mage of those most persecuted (and unwanted parts of ourselves), grovels faintly for air or release or even the minutest chance of escape. He crawls defeated, but snake-like, slowly off stage, prisoner, and slave, eaten by the forces of negativity and hate.

Cabaret is history and it is now. Fascist dogma still tries to gain its stronghold: in our country against hard-won civil rights, and in our minds against the freedom to love.

We can’t give up the fight.