LEO HURWITZ

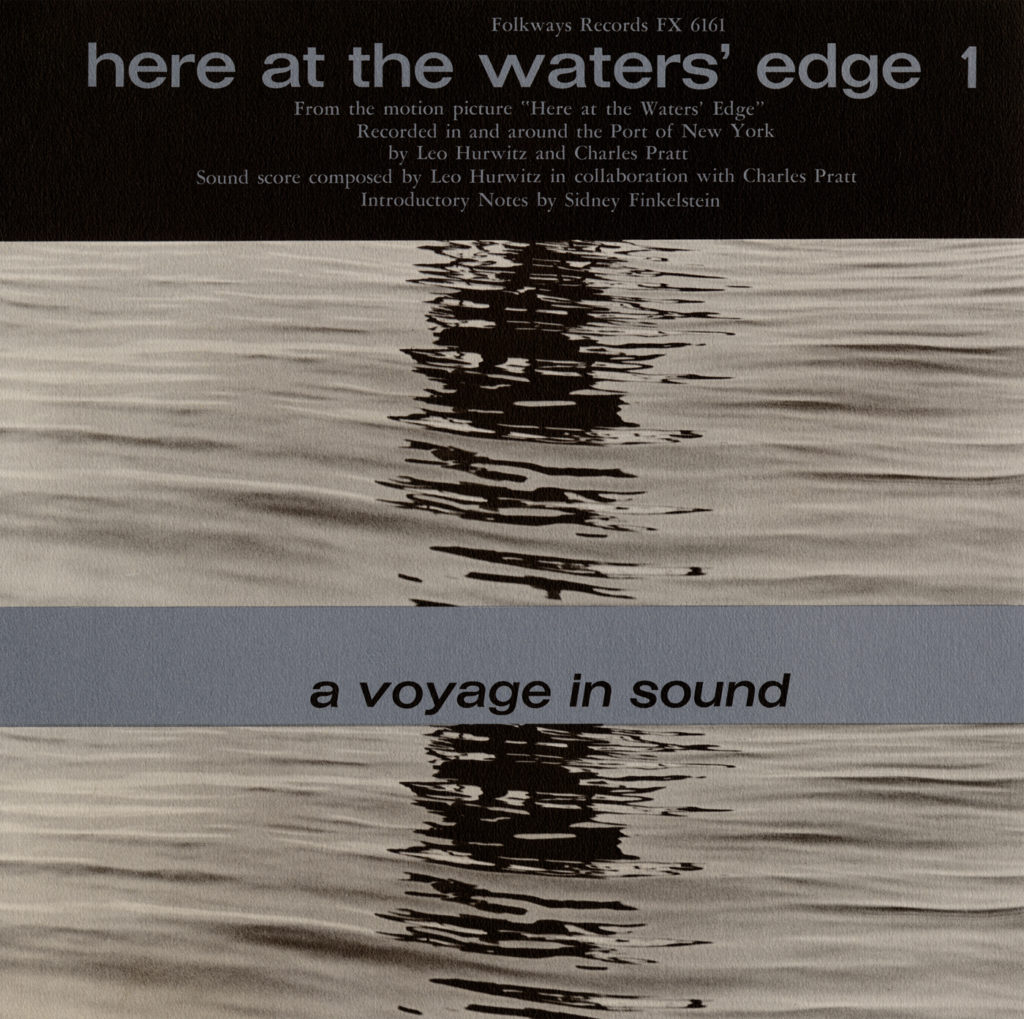

HERE AT THE WATER’S EDGE 1961

Seeing What Needs To Be Seen

Leo Hurwitz’s film, Here At The Water’s Edge (Watch Film), features the 1960 New York City’s waterfront. Made with photographer Charles Pratt, the film is a cinematic poem to the people who work on the water. Pratt, who largely financed the film, made it possible for Leo to use his vision as an artist and filmmaker while the blacklist still over-shadowed his life and ability to work in other areas. Here At The Water’s Edge, a film without narration draws our attention to the often-neglected life in, on, and around water – as well as bringing into view what workers on the water give us. Leo, in his own work, was always concerned with seeing what is happening in spaces in the world where others fail to look.

In one of his childhood memories, Leo was three, distracted, and missed his semi-final run for a potato race he wanted to win: “The threat of missing something by virtue of not being alert haunted me for many years.” Afterward, Leo’s eyes never diverted from the truth he believed must be seen.

Ingela Romare, in her interview with Leo, comments on the close attention he pays to the matter of “seeing” in making Here At The Water’s Edge “… we meet something that is very special for Leo Hurwitz, a desire to give us, the audience, an immediate experience of what he, himself, has seen and experienced – to share, in a loving way, to make us see, what is there …”

Seeing What Is There

Seeing what is there isn’t easy when it comes to such atrocities as fascism and racial hatred; the consequences of which Leo brings to light in his films Heart of Spain, Native Land, Strange Victory, and The Museum and the Fury. Although he takes us into nature in Here At The Water’s Edge, the nuances of Leo’s compassion and commitment to the rights of the working class, people that need to be seen and heard, are just as evident.

Here At The Water’s Edge begins with Herman Melville’s quote: “Yes, as everyone knows … water and meditation are wedded forever.” We are taken into a meditation on the rights and needs and contributions of people who work on the water.

We hear a symphony of ocean waves crashing against the shore. These waves move rhythmically, in and out as they meet the shore and then recede, just as we might see and then forget. Cattails line the water’s edge. A lone blooming plant quivers in the wind.

It’s peaceful here. Our presence, as spectators, is accompanied by Henry Cowell’s orchestral music. We spot a fishing boat not far from the shore. A seagull flies above, calling to be heard.

What is it we might see and hear? For each of us, the message will be personal. This is what Leo intends. We’ll find that message in Here At The Water’s Edge in its five separate passages.

Passage 1: The Inland Waters

Water seeps and flows between rocks. There is foam and ice, a winter’s water. A tugboat whistles; other boats surround it; there are men working in the cold on the water. Leo gives us a window – an entry into a workingman’s life.

A discarded bottle floats quietly, forgotten. Is that bottle carrying my message? What will I find in Here At The Water’s Edge?

Seagulls fly over, making their sounds, peaceful above, while the work down below makes the waters rough. We see debris, floating away, things people abandon; now lost and forgotten.

What are we to remember? That life along the water is just as important as life in the city? Not forgetting the meaning of those simple things in nature, or the men who perform their modest labor quietly behind the scenes of everyday life.

Here At The Water’s Edge

A voice speaks out via megaphone. Dark, murky water laps against a wooden pier. Night turns into day, with the pink of the sun rising. More debris of what isn’t wanted floats downstream contrasted with hopeful, lilting voices of children playing and singing. These are the things of life. And, in life’s center is work.

The work we see is work of common laborers, the workingman whose rights Leo always supported and protected. These workers are the ones who do what is needed on the water’s edge, the port of New York City. They solder; they use cranking, screeching pulleys; we hear the various harbor noises of men using machines and doing their work.

A freight train whistles from tracks close by, a tug blows its loud and demanding horn; a boat captain turns his boat’s wheel; and a barge moves more quickly than we imagine it could – with a pretty, smiling woman’s hair flying in the wind.

In contrast, as a cruise ship waits to depart; we are given a glimpse of quiet through the petals of a flower on the water’s edge, letting us know that more peaceful waters still exist not far from the lives these busy workers live.

Passage 2: The Changing River

The river is a place of change. The river edge of New York City’s busy ports starkly contrasts with the beatific painter’s scenes from yesteryear. A peaceful sea town appears with people lounging on benches, windmills turning slowly; Native Americans in feathered headdresses canoeing on the water. This is a painter’s image of a long-ago time. We come back to now.

In the now of 1960, we hear hammering. We see shadows of the docks reflected in the water. A dog barks. Men’s voices talk. A train chugs by. A boat’s horn honks. A pink tugboat moored in the harbor is ready to work. A bridge spans the water with cars moving quickly across.

City life. Lights flash upon dark waters and a deep tugboat horn blows once more, alerting us to daybreak. The camera pans across legs of many men, walking and working in early morning dawn. The tug’s horn is a signal of men laboring on the water; the hard work of a major city’s port; receiving and shipping cargo every day.

Passage 3: The City’s Edge

Every day, there is work on the water’s edge. A man, shadowed, walks across the pier with a hammer. Another man walks down the plank of a large freight ship, its name in large letters: Santa Monica. Another man’s shadow reflects against the red/pink hue of the ship’s bottom. We see the black and white of Santa Monica’s deck, its beams reaching high above dark water, far into the sky.

A chain pulley lifts the boat’s anchor. A man in hardhat works. A seagull flies overhead. Another man, protective gear covering his face, solders something on the peer, sparks shooting out, as the ship Santa Monica pulls out to sea.

In the harbor are working boats with other names – Dalzell and M. McAllister – highlighted against the city’s skyline. The propellers of a helicopter whirl. But the busy working harbor is only part of life along the water’s edge.

Boys play baseball in a park close by. A boy in a red shirt catches a ball; another in black and white plaid hits that same ball with a bat. We see the young batter’s back through a chain-link fence and, before we know it, we’re inside the fence, a part of the game. Older men sit together on a park bench, watching children play on a slide. These are working-class people. There is play and there is work on the water’s edge.

The Workingman’s Life

A freight train carrying stacks of lumber whistles its arrival. A pulley lowers the incoming cargo onto the dock. Hands, men’s hands, guide that cargo to its destination. A man hops onto a passing freight train and helps bring in its goods. A white sign tells us where we are. This is “The United States of America.” This is the workingman’s life – on the water’s edge.

Leo’s camera captures serious faces, men intent on work. Hardhats hammering, guide steel beams, repair New York City’s docks. We see dirty waters filled with the debris of busy industry. A worker smokes his pipe. These men; faces, weathered from working on the water.

A captain guides his barge into the shore as the Statue of Liberty’s emblematic hand reaches high, welcoming us to New York City – America. The pinnacle of freedom, she is. But, is there liberty? It’s a question Leo Hurwitz asks in many cinematic forms. Yes, these men have work. They do their work seriously; they don’t stop or lounge. Yet, do they have the same rights and benefits as others? Do they have fair pay, fair hours, for all their work on this water’s edge?

The camera pans to yellow daisies with their dark black centers, in the midst of hard labor. A daisy – bright and hopeful (its hope sometimes marred) stands tall on the water, against the Empire State Building and the New York City sky.

Passage 4: The Surrounding Shores

Food. Food is another commodity that enters the docks on the water’s edge. These men help feed us.

For now, out of the shipyard, we see a workingman’s hands packing bushels of potatoes from a large cart. Excess potatoes spill into the water mingling with an overflow of bananas, floating near the surface. A poor Black man scavenges this welcome food. There is hunger too near the water’s edge.

The waves, pink-tinged, move in and out in their unchanging rhythm. White foam caps and daisies blow hard in the wind. A freight train does its work. Schwartz Chemical Company’s plant alerts us to the dangers of pollution, other kinds of spillage less innocent than food. The daisy stands strong along the water’s edge. There is hope for humankind in Leo’s films, against the dangers and loss of innocence.

We see mothers pushing prams, children and flowers, laughter and big smiles on swings that seem to fly high into the sky and back again. And, there is happy chattering: “Wait for me, wait for me.” A merry-go-round spins lonely after a little girl jumps free.

We see the city, families, and commerce. Hard labor contrasts with nature, not ravaged so far – but threatened by obliviousness to what might contaminate life. A bridge connects people with nature, with waters that bring the supplies we need to survive.

Passage 5: The Island City

The Statue of Liberty raises her torch. Smokestacks breathe smoke; water swirls. A boat rests quietly within the cattails near the water’s edge. The moon, pink-tinged, lights the sky. Waves and tides continue their rhythms, the sun sets and rises, more steady than the varied ebbs and flows of all the different parts of a major city – human, machine, and nature. And, the seagull flies free through the skies.

The city waits for its people. Will we find liberty and equality for all? That is the age-old question and it repeats in every decade and every century.

The film ends with Walt Whitman: “I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence, just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt …”

I am just one viewer like the lone flowering plant on the water’s edge in the film’s beginning. I return to the discarded bottle in Passage 1. This message is mine. Maybe it’ll resonate with you, as the tides come in and go out again:

These are the rhythms of change and these rhythms carry questions: Can we feel for each other? Can we see those who might be forgotten? Can we bring into the light people who live in the shadows, working hard by the water’s edge, or anywhere else? A day ends and a new day dawns. A daisy, in Here At The Water’s Edge stands tall and strong on the shore: reminding us of hope if we don’t forget.