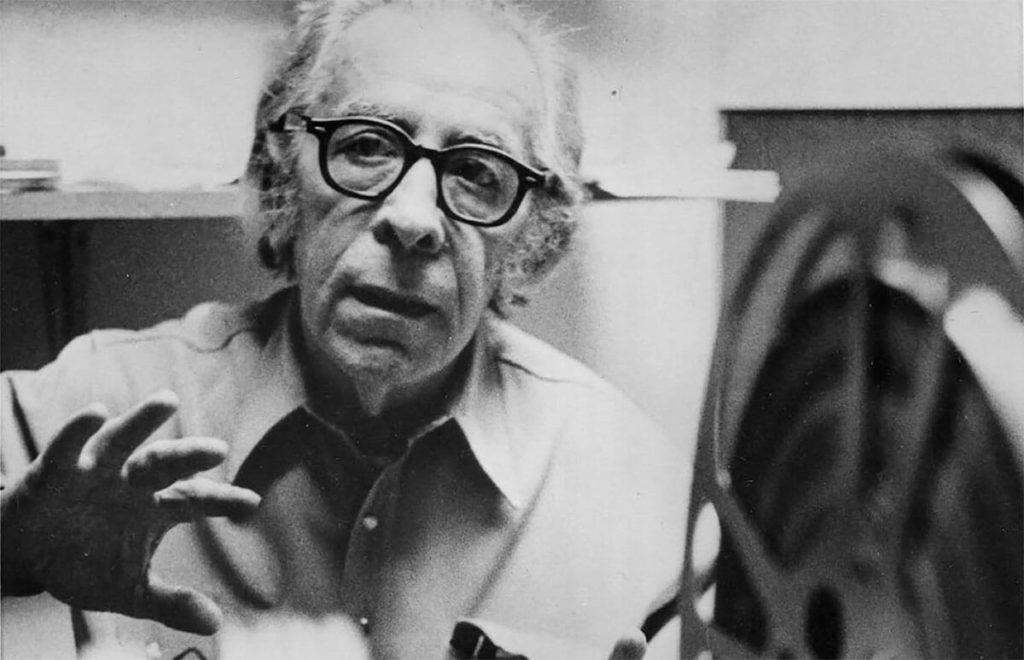

LEO HURWITZ

THE ART OF SEEING 1968-1970

THIS ISLAND

Seeing With Our Hearts

This Island, a Leo Hurwitz film (Watch Film)- directed and edited by Leo with co-editor Peggy Lawson and cameraman Manfred Kirchheimer – is a film about a museum: The Detroit Institute of Art. But, This Island isn’t just about a museum. It’s about discovering the meaning in art. And, that requires looking deeply and openly to see what is there. If we let him, Leo Hurwitz has a few things to teach us about seeing. We are witnesses to that fact as we watch all his films. Light and the City and Discovery in a Landscape in his The Art of Seeing series are good examples. This Island is no different. Leo helps us think long and carefully about love, acceptance, and truth.

In This Island, Leo shows us how to look at art; how art can take us to places we’ve never fully explored, mostly inside ourselves. Considering this, Swedish filmmaker and cinematographer Ingela Romare introduces us to why Leo and Peggy were drawn to make This Island and to the particular form the film took: “They wanted to pull down the barriers which prevent an immediate and spontaneous meeting with a work of art … [and] they take us carefully into this island of collective human experiences.”

Conceiving This Island

Openly receiving what museums have to offer isn’t always the easiest thing to do. Leo knew that. So, when The Detroit Institute of Art asked him to make this film, he said to them: “let me make it about what’s in the museum, what the content is. Let’s use it to discover the meanings, the experience of art – to reach people with things they might not have felt. A lot of people are closed off to museums. They are a far-off place, they push you away …”

I know that feeling. When I walk into a museum, I’m immediately overwhelmed. Where do I start? Do I have to take in everything in one visit? Leo says, “No.” He had his own method for beginning a film, similar to what is required when viewing art:

“Once I got them to agree to the idea, I sat down to write notes to myself. My way of getting to a script for a film [is] … first to be free in my mind.” Leo shared with Ingela Romare where his musing took him.

To illustrate, here are the results of Leo’s musings to help you enter into the substance of the film. Through his notes to himself, Leo came upon 3 emotional considerations that underlie This Island’s detailed exploration of the contents of The Detroit Institute of Art:

1. Relevance

“These notes … are a kind of inner self-to-self-dialogue in which I am asking myself questions. One of the questions I had is the word “relevance,” meaning ‘what is the relevance of the art, that is, the art in the museum and the people around it?’’

Truly, finding this relevance is rooted in each person’s feelings and emotional histories: “If there’s someone you hate, love, or something you enjoy, you’ll find that hate, love, joy, in the museum. The museum is an encyclopedia of feeling, perception, of particularized knowledge. In a sense, the nub of the universe of life.” These realizations led Leo to several questions:

“What is art … and why lead people to it? [Viewing art] is a process of great enjoyment because I don’t have any boundaries … I just have to discover what’s inside myself … Then, I came to the theme of … what is the working energy of paintings?” As Leo dialogued with himself, on November 20, 1968, he decided that the central energy in art is – love.

2. Love

Yet, love is a complicated thing. Those we love need our interest, curiosity, desire to know them, and our patience. Art is no different: “…. The painting of a subject, the canvas, must be loved. Otherwise, it would not be done. It’s too intricate, too demanding, too involved, in its creation. In order to get by all those difficulties, you have to love it…”

Hence, in these poetic words, Leo tells us what an artist must bring to his work: “the attention, the intimate search; the caress of the eyes. The process itself is … the love of the real, the truth, of what he sees and knows … love in good art is not a romantic thing that eliminates insight, criticism, and hate. On the contrary, [the artist] creates this content, energized by the love of truth.”

As an artist himself, Leo was familiar with the truth it takes to create.

3. Truth

Art lovingly, creatively, and honestly expresses what emerges when an artist reaches deep inside to find his (or her) emotional truth. Indeed, this is the kind of truth Leo Hurwitz brings to his films. It’s also the kind of truth he invites us to bring to our own experience of art. Such inner reaching is the source to feel our way into art. If we are open, we might be transported to new inner places and realizations. Yet, this isn’t the way many of us were taught about art in school. Or the way museums are set up, making us feel rushed and without room to stand still, take in, or feel.

So, in This Island and with his words, Leo calls on us to do something quite different – to give in to a long, slow meditation before a work of art:

“Stand in front of the painting, and what do you experience? Go away and come back, you experience something different … this is a painting the artist took months, maybe years, to complete. There’s a complexity of life that went into it and unless you give it the time to come out, it isn’t going to … if it’s going to be an experience that has any enjoyment, any feeling, and any growth of knowledge and so forth, then you’re just going to have to give yourself to it.”

This is love and this is truth. And, maybe, as Leo suggests, we won’t look at one hundred and fifty paintings; we’ll only look at five.

Pre-History & Beginnings

As This Island begins, we move through the gates of The Detroit Institute of Art. These are the things my eyes center upon, the first things I see: the Eye in a painting, a sculpture of a male face, a primitive mask, and a medieval piece of armor. And, I see the prehistoric figures at the museum’s entrance, a fertility god or goddess, and an embryo in the womb.

This is where we all start. We begin with our own pre-histories. I begin with mine. This film is my great-uncle Leo’s film, my grandfather’s youngest brother. I see where I’ve come from. Where we each go is up to us. The question is: can we go with our eyes open and learn to see with our hearts? Can we see clearly the people we meet?

There are many and different faces captured by each artist and by Leo’s camera. These faces take us into human experience. We relate. In spite of our separateness, we are not islands. And, we all begin not knowing differences.

People: Now & Then

The museum is full of people, people now and people through the ages. So too, there are lovers, Greek runners on an urn, a figure in a garden – and hands. Can we reach out, reach into the experience Leo offers us; the one the artist brings to us through each painting and each sculpture?

Now, there are Eyes, many Eyes; eyes that look out from pieces of art. Indeed, these eyes are the artist’s vision, the eye of Leo’s camera, and our own eyes looking. What do we see when we look? Do we see differences or commonalities? Are we open to seeing the truth?

Next, we’re now out on a street. People walk. A taxi goes by. People wait to cross. This Island superimposes photos and images of art upon a daily slice of life. The stuff of human experience, the place where the inspiration for art happens, as multi-textured and multi-faceted as life itself.

But, in contrast, on the street, in our simple lives, we too often see only one dimension. Yet, human feelings are as complex as the face of a woman captured by Leo’s camera – short, dark hair; sunglasses, a faux fur white jacket to ward off the Detroit chill. She walks, stops; looks directly into the camera – confused, bothered; not happy.

Here, everywhere, are nuances of human emotion. We all have the same kinds of feelings, in varying personal forms. And, we bring them to our lives, to making art or to witnessing art after it’s made.

Looking and seeing, we enter into an experience that is not entirely our own.

Seeing

Will we see or will we not? The camera takes us back to the face of the woman with black hair and sunglasses. She now wears an angry, troubled look. Is she upset at being seen? Maybe she feels this camera is an intruder? So, she looks away as if to say: “You will not see me.” Maybe she’s the one refusing to look.

If we look, there are difficult things to see. And, art shows us exactly where human life is lived. The artist takes us into tough places; much more complex than the picture that now comes onto the screen. Of children innocently playing with hula-hoops in a park, their faces open, not yet jaded with reasons to distrust.

Art exposes human life in places that are raw. Feelings sometimes overwhelm; as they must for the man we see in the next painting; naked, flayed backward, drowning, pushed under the water by enemies. He’s a slave, helpless, not in control.

Next, we follow the camera’s eye onto the street again. Whites and blacks picket together. Black Power is spray-painted on an outdoor wall. Inside the museum, we see a painting of hard labor, black and white skin working in tandem. In the outside neighborhood, children sit beside each other on a stoop. Blacks protest with signs: “We need teacher’s aides.” All of us need help.

Leo’s camera focuses on a broken window with curtains still fluttering inside. And, in This Island, he helps us break down the barriers to our commonalities, to seeing how others feel.

Together, Not Apart

Human feelings are the same. Our differences shouldn’t separate us; but sadly, they sometimes do. We see it in art. See it on the streets. Can we come together – like the people who stand before a painting at the museum, taking it in, talking about what they see?

The camera takes us back to Greek runners on an urn. An ancient sculpture shows a woman’s kind, but pensive, face. The stern, unrelenting face of a man is carved into a pre-Columbian figure. A Botticelli woman is sleeping. Can we be awake enough to ask: are we kind or are we un-giving?

In art, we see people. We see them in the paintings and sculptures at The Detroit Institute Of Art. See people looking. Eyes, there are eyes, in all of Leo Hurwitz’s films.

If we look, we see people in pain; powerless; mistreated; people fighting for their rights, needing our help.

The last image in This Island is Van Gogh’s self-portrait. Leo’s camera zooms onto his face, again and again. As the film comes to a close, we are left with Van Gogh’s piercing eyes. In this film, Leo Hurwitz has given us a chance to turn our eyes inwards, to see clearly, and to feel.

There is love in creating art. Love, too, in knowing that others are more like us than we think. With This Island alongside his The Art of Seeing series, Leo teaches us that it is not impossible to see with our hearts.