LEO HURWITZ

IN SEARCH OF HART CRANE 1966

Reflections On His Suicide

& His Childhood

Leo Hurwitz’s penetrating and poetic script and his camera (with the assistance of fellow cameraman Manfred Kirchheimer) (Watch Film), follow John Unterecker, Hart Crane’s biographer (the 800-page “Voyager: A Life Of Hart Crane”), through Unterecker’s researches into Hart Crane’s life. In Search of Hart Crane is composed primarily of fascinating interviews with friends of Hart Crane – those who knew both the troubled man and the poet well. How do we find someone – the real person hidden inside? The one who’s been hurt/who struggles/who has his dark demons? And, especially, how do we understand Hart Crane’s suicide; the suicide of an otherwise talented, lively, vivacious, and successful young poet? The film tries to answer these enduring questions: What happened to Hart Crane? Was his suicide inevitable? And, if so, why?

In Search of Hart Crane

Our narrator (the voice of Gary Merrill) in In Search of Hart Crane introduces us to the beginning and end of Hart Crane’s life: “Harold Hart Crane was born in Ohio in 1899. A toenail in the last century, as he later wrote. In a life short, intense, and filled with struggle, he was to become America’s unique and great poet of the twentieth century, a direct inheritor of Walt Whitman.”

Yes, Hart Crane’s life was filled with struggle. There was financial struggle, to be sure, that of any writer without a day job. But, Hart’s real struggle originated in childhood, lost in the midst of two disturbed and warring parents, their confusing and twisted sexual reunions, and their complete inability to make emotional room for him.

Hart’s businessman father, Clarence Arthur Crane, founder of the Life Saver candy, never understood Hart’s artistic nature. His mother, Grace Edna Crane, left him as a baby, came back, either impulsively left him again or took Hart out of school to accompany her on her travels. She expected devotion. Her needs were primary – not his.

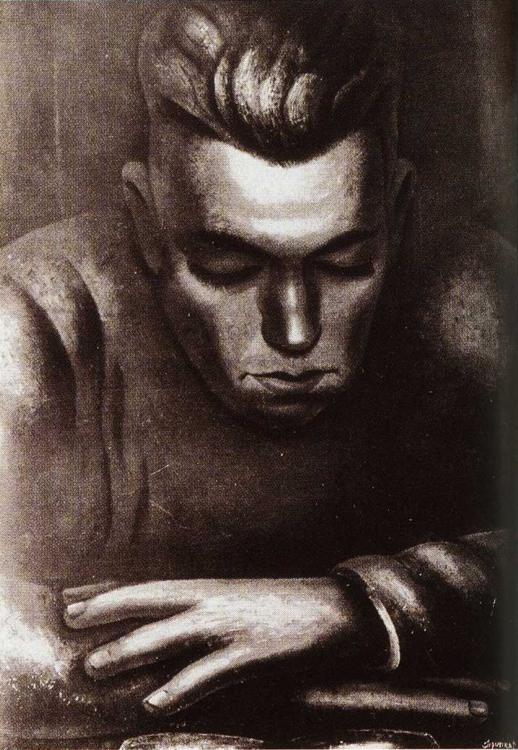

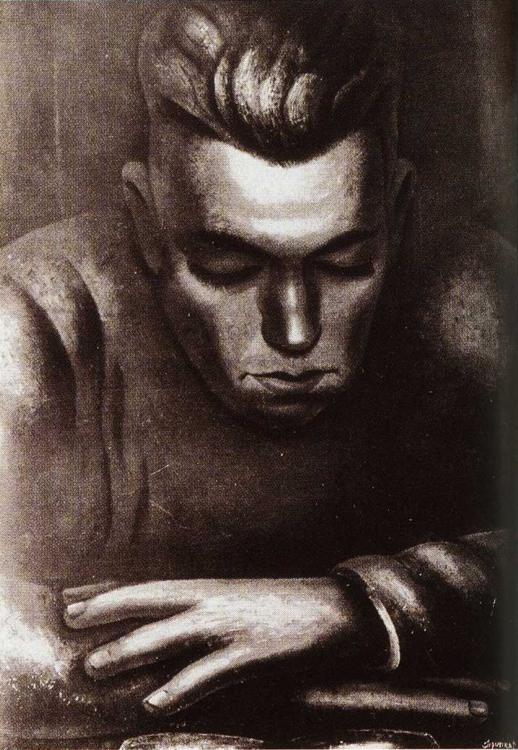

Now he was dead. We see images, newspaper headlines, Hart Crane’s face, serious; and sad: “Poet Lost At Sea; Disappeared en route from Vera Cruz to New York.” “At age 32, drowned.” “Son of Candy Store Founder Dies on Voyage from Mexico.”

Our narrator continues: “In the Spring of 1932, Hart Crane’s life ended in the shark-infested waters of the Caribbean, joining the sea, a persistent image of his poems.” More newspaper headlines read: “Death of Hart Crane at Sea is Confirmed: Friends Hint Suicide.”

Hart Crane Not Simply Lost At Sea

So. It wasn’t simply that Hart Crane was lost at sea. He was lost in a different sort of way – in a sea of troubles that began as a young child; troubles he never found a way out of, except for ending his own life. The fantasy of death wasn’t new. As a teenager, he’d once slashed his wrists and another time took eighteen of his mother’s sleeping powders. Suicide involves the fantasy that death is the only way to stop feelings that are too overwhelming to feel.

In, “At Melville’s Tomb,” not published until 1933 after his suicide, Hart wrote:

Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men’s bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death’s bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph…

When it comes to suicide, the question we always want to ask – is why? Biographers and psychoanalysts look for the “livid hieroglyph;” the clues. Livid is, of course, angry – and Hart was a rageful man. He was also unbearably sad. The hieroglyphic clues a psychoanalyst looks for hopefully lead to understanding – before a successful suicide takes place.

Biographers

In Search of Hart Crane begins with John Unterecker in the Columbia University Library going through Hart Crane’s manuscripts and correspondences from 1925 to 1932: “The biographer’s job begins with piecing together fragments,” our narrator tells us. So does a psychoanalyst’s. As I watched In Search of Hart Crane unfold, I found myself piecing things together in my own way.

Unterecker searched through photos and the attic of Hart’s maternal grandmother, for family portraits of those known and unknown. He, the biographer, “pores over these fragments, until he knows Crane’s life day by day … until he may be able to spark new revelations. Then, [the biographer] moves out of the library to Crane’s friends, to people who knew him.”

Those friends Unterecker interviewed, the friends Leo Hurwitz’s camera follows were: Charmion Von Weigand, Painter: Gorham Munson, Critic: Waldo Frank, Author; Samuel Loveman, Poet; William Lescaze, Architect; Susan Jenkins Brown, Editor, and Author; Malcolm Cowley, American Novelist, Poet, Literary Critic, and Journalist; Slater Brown, Writer; Margaret Babcock, Translator; Solomon Grunberg, Philosophy Scholar and Lay Psychoanalyst; Margaret (Peggy) Baird Cowley, American Painter, and Hart’s fiancée at the time of his death, after her marriage to Malcolm Cowley ended in 1931.

Psychoanalysts

A psychoanalyst doesn’t move out of the office but listens for how friends and lovers come in and out of a patient’s thoughts. She listens for meaningful fragments in fantasies, dreams, and associations so that she knows someone’s internal life, piece by piece.

As a writer and psychoanalyst, I have taken fragments from the extensive interviews that make up the whole of In Search of Hart Crane; fragments that might provide clues to what Crane struggled with at his core; what led him to his demise.

For John Unterecker, the search takes him everywhere: “His headquarters is the library. He works with everything he can get his hands on because Hart Crane is more than these shadows, more than his letters, manuscripts, published poems … he looks for clues of private thoughts in the books Hart Crane selected from boyhood with their passages marked or underlined.”

For me, a highlighted line from Byron stands out: “Nor are my mother’s wrongs forgot, her slighted love and ruin’d name … her offspring’s heritage of shame … but she is in the grave, where he, Her son, thy rival, soon shall be …”

Mothers & Nightmares

The stereotype of psychoanalysis is that: “everything goes back to the mother.” Sometimes it does. Mother is the first object of love and need. That’s not to say that Hart’s father wasn’t a part of his problems. We know, from interviews with friends, that he hated his dad. But, his relationship with his mom was much more complex – going back to her abandonment in his infancy.

Another telling poetry line, one of Hart Crane’s own (one that Slater Brown heard him quoting) says more: “Where the cedar leaf divides the sky, I was promised an improved infancy.” Crane’s parent’s troubles, his mother’s leaving him, her erratic moods – this troubled infancy – must have been at the heart of the depression Hart was running from.

Hart Crane’s Dream

He once had a nightmare about his mother (a nightmare he told to fellow poet, Samuel Loveman): “… he was a physiologist, searching through [her] entrails; something was hidden there. A horror, not crude – something hidden there, something he was searching for. I think it was the core of his existence.”

Hart Crane’s relationship with his mother, Grace Hart Crane, was something of a nightmare. He must have felt disposed of as a baby. Later in life, he was the one in control of the comings and the goings. He broke things off and reunited with her over and over. No longer the passive victim; he became the director of their separations.

We can all get rid of our real parents if we wish – but not the mothers or fathers that live inside our minds. Hart felt undeserving of love. In 1931, in Mexico on a Guggenheim Fellowship, he fell in love for the first time with a woman, Peggy Baird Cowley: “I don’t deserve it, he wrote her. I’m just a careening idiot with a talent for humor at times, desecration at others.” This was the legacy of his infancy. Perhaps, hidden inside, he felt like “shit.”

How Infancy Lives On

As Leo Hurwitz follows John Unterecker’s interviews with Hart Crane’s friends, we find pieces of the trauma of Hart’s early life. His childhood friend, painter Charmion Von Wiegand said this:“Hart was born into a family in which he had nothing in common.”

We see photos of him as a baby, his serious face – a baby detached, lost amid his parent’s vicious quarrels. Our narrator tells us: “The artist appeared at the turn of the century, the amiable child, affectionate, clever, a child isolated from other children; out to please the grownups; a child often separated from his parents.”

Because of these beginnings, there was, raging deep in the undercurrents of Hart Crane’s mind, a very dark depression. He had a panicky hysterical anger about being left alone.

Desperation when Alone

Malcolm Cowley said of Hart: “It’s true, he’d become desperate when he was alone. It would get to the point that he’d start throwing furniture out of the second-story windows and he’d run himself out of friends … At parties, he’d get in a desperate frame of mind and begin throwing phonographs and records.” He once threw his typewriter out the window; retrieved it, and threw it out the window again.

Samuel Loveman was with him at one of his desperate moments: “I grabbed him when he tried to fling himself over the roof and pulled him back. I said: ‘you so and so … never do that again.’ He said: ‘I might as well, I’m only writing rhetoric.’ That’s the only confession of failure I ever heard.”

Yet, he must have felt a failure in his parent’s eyes, dating deep back into the recesses of his infant mind. An unwanted baby; a child who couldn’t measure up to his father’s expectations, being so different; a child who could never please his mother, no matter how hard he tried – a child who had no one to help him with his complicated feelings.

Exuberant & Dark Moods

Many of Hart’s friends experienced his highs and his lows. His moods were often erratic. He could be exuberant or dark. When someone is fighting deep depression, exuberant highs can be attempts to shed the darkness.

Gorham Munson lived closely with Hart’s varying moods. They met at Joe Kling’s Pagan Bookshop in Greenwich Village and became friends: “On the first of February, 1923, Liza Delza and I took our first apartment together. We’d been in Greenwich Village for four days when Hart Crane arrived from Cleveland with valise. He was a difficult man to have in a small space. Hart’s feelings he always considered were the feelings of everybody around him. If he felt high and exuberant, well of course everybody else did too; if he felt tired and grumpy, then the whole world did. So, the whole environment had to correspond to Hart’s psychological states.”

Susan Jenkins Brown describes him as having: “a great deal of joy about all aspects of life.” Yet, there was a severe division in Hart. He was just as often morose, depressed, and full of rage, especially when he was drinking.

Unterecker asked Slater Brown: “Do you think he was disturbed, thinking his friends didn’t know what a fine poet he was?” Slater Brown replied: “Oh, he had moments and he used to mention it when he was in one of his rages, but I think on the whole we were always sympathetic and giving him praise …”

Terrible Self-Doubt

Likely, Hart’s self-doubt made it difficult to believe their praise. His father had a part in that. Hart’s father pressured him to be in the Candy business, often displeased with Hart’s choices. Unterecker asked Samuel Loveman: “Was Hart afraid of his father?” Loveman replied: “He wasn’t afraid, he was resentful.”

After Hart’s father died, Slater Brown ran into him in Washington Square; home, from his fellowship in Mexico for his father’s funeral: “He was full of doubts. Had he ever written anything of lasting value? He didn’t know if he’d ever write anything again. Seemed depressed and in a hopeless state of mind and a few days after that, I think he returned to Mexico.” About his father’s death, he said to Peggy Baird Cowley: “there is that momentary pain; that fear. It fills the whole of you.” She wondered if he felt it when he died.

Ever-Present Fear

That fear is something Hart lived with his whole life, I imagine. Fear of being desperately alone; leftover from the helpless, lonely, separations he’d had from his mother as a baby and small child; separations that convinced him he wasn’t good enough. Peggy said, before he died, he slashed his poetry with a razor. This is revealed in, In Search of Hart Crane.

The night before he jumped overboard, Peggy tells us: “… he was on this drunken rampage. The next morning, Hart came in and said: ‘Everything is lost, I’ve got to go.’ I said, nonsense, let’s go have some breakfast. He said, ‘It’s too late for breakfast, I said ‘we can have some’ … they brought a menu to him and he ate an enormous meal. I guess he wanted to be filled with something … then I went back to get dressed for lunch and all of a sudden the boat stopped … I gave a scream and I said: ‘Hart.’”

Suicide: Inevitable Or Not?

Unterecker asks the million-dollar question in In Search of Hart Crane: “So much has been made of the inevitability of Hart’s suicide, but it doesn’t seem inevitable to me at all, does it to you?” Margaret Babcock answered: “Yes, it does, for psychological reasons.” Waldo Frank said: “He’d lost his hope. He’d lost heart … lost faith in himself, and the dismal prospect of New York in 1932 had a great effect on him.”

Charmion Von Weigand didn’t think suicide was unavoidable, though: “if someone had taken care of him. [But] he couldn’t make a new beginning…” The ending of “My Grandmother’s Love Letters” gives us a clue to why: “… and I ask myself: ‘Are your fingers long enough to play old keys that are but echoes?”

His fingers weren’t. Hart Crane could never resolve the old echoes of his childhood. To Charles Chaplin, an idol of Hart’s, he wrote: “We make our meek adjustments … for we can still love the world, who finds a famished kitten on the step.” I think Hart was that famished kitten, hungry for love – an emptiness that was never filled. The tragedy of In Search of Hart Crane is: his hunger was never found.

Hiding His Hungers & Sadness

Psychoanalysis offers another set of fingers to help reach the echoes of old keys. Hart Crane didn’t have that help. As In Search of Hart Crane ends, a line from one of Hart’s poems comes onto the screen: “This fabulous shadow … only the sea keeps.”

That shadow is the darkness within which Hart’s hungers and sadness were hidden. Poets write from the deepest reaches of their inner selves. Perhaps, it was his sadness Hart was trying to understand. He once wrote: “I have seen more tears than I ever expected in this world … I have shed them through others’ eyes.” I wonder: did he drown in an ocean of tears, not knowing what to do with them?

The irony and tragedy of Hart Crane’s death are that his father was the Life Saver man. Yet, Hart jumped off an ocean liner with nothing to keep him afloat, and no one to save his life.