LEO HURWITZ

DIALOGUE WITH A WOMAN DEPARTED 1972-1980

A Poem Of Love To A Wife

Who Lived In Protest Against Hate

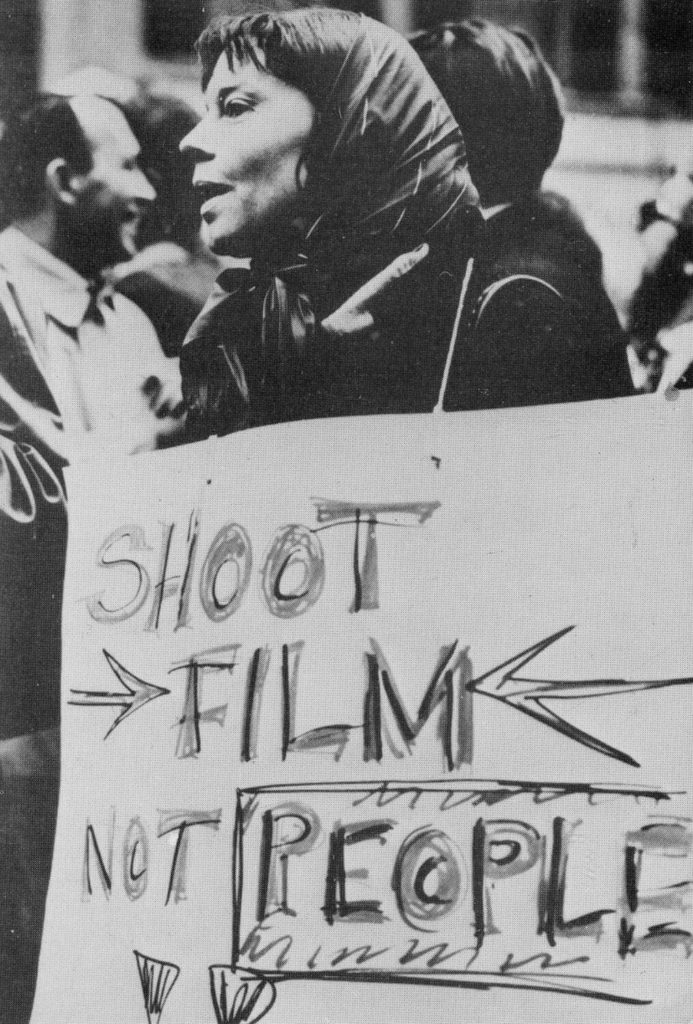

Shoot Film, Not People: this is the poster filmmaker Peggy Lawson, Leo Hurwitz’s wife, carried during a march against the Vietnam War. As we watch Dialogue With A Woman Departed, (Watch Film) Leo’s 4-hour love poem to Peggy, we come back to this sign again and again. Again and again, we come back to Peggy: marching in protest, hair tied back with a bandana, face determined, alert, and wise – a kind of wisdom not so easily won.

Peggy’s Texas childhood was difficult. Part Native American, she experienced poverty and discrimination. Her sensitive, intelligent, aware nature detected even then the unfairness of poverty, the struggles of those in minority, the ways she and those she loved were treated. From childhood on, questions about the forces of hate haunted Peggy.

Later, Peggy and Leo fought these forces with their films and their activism. When Peggy died in 1971, Leo fought a different kind of war – one of loss and grief. To do so, he shot this film:

Making Dialogue With A Woman Departed

“This is the film I must make for you, Peggy … the film I had to make. Otherwise, how would you continue? Continue in tears; in loss … continue in the black hole inside me … I must make this film of you to continue you, now in me; to move you into the world that touched heavily, lightly, your heart, delicately, passionately, your heart … the image is on film.”

The images in Dialogue With A Woman Departed are images of a life they shared. They are images of Peggy as child and adult; of Peggy who continued to live inside Leo and who now lives inside each of us as we witness her through Leo’s eyes. This film, this dialogue with the woman he loved, is a poem of remembrance. In a word, this film is Leo’s way of working through his grief.

Dialogue With A Woman Departed was written, photographed, edited, and directed by Leo Hurwitz. The film took about 9 years to make and weaves together earlier films and earlier life. Leo, and Kaiulani Lee (for Peggy), narrated the film. Tom Hurwitz (Leo’s son), Nelly Burlingham (Leo’s third wife), and William Kruzykowski assisted. The film was partially funded by The National Endowment for the Arts and the New York Council on the Arts. The film won the International Film Critics Award at the Berlin Film Festival in 1981 and it is regarded as one of the great documentary films of our time.

Leo: The Woman I Love Is In Me

Images. The film begins with a tree trunk in a snowy landscape. A dog barks, a violin plays, and the camera pans upwards into the tree’s branches. We hear Leo’s voice grieving and remembering: “With memories of flesh, of laughter, of eyes that reach, I pay my respects to you sweet woman of the earth; woman of the landscape, of the autumn, of the water, of the grass.” Snow creates designs in the bark of the tree.

Now, it is winter. Leo’s voice introduces us first to Peggy’s death and, then, to her life: “Peggy lived ‘til September, to the turn of the season. Her ashes are here, at the roots of the tree. In another season, her eyes traveled into its branches, dwelt among its leaves and the landscapes framed there … The tree holds its design of life, channeling the flow of energies from earth and sky into one living thing … thus life dead, terribly dead, transforms itself to life again … the essence of a person has lived itself into me, into those whose memories hold her winter design.”

And, in Dialogue With A Woman Departed, we come to know Peggy through Leo’s eyes – the ways she lived in him; the child she was; the woman she became.

Peggy: “The Child I Was Is In Me”

A close-up of Peggy’s face comes onto the screen. We hear the voice that would be Peggy’s if she were alive: “The child I was is in me.” Quickly, we see Peggy as an adult, in protest, carrying her sign: “Shoot Film, Not People.” The child Peggy had her reasons to protest.

Peggy’s voice: “What I remember of the trail of tears, I have taken with me in all my wanderings, to many places, many tribes … what I remember of the trail of joy, I have taken with me in all my wanderings. I have wandered into my own past, moving back and forth in memory and time … wandered with terror, and with strength … with submission and love … anger and shouting against war and Presidents … wandered comrades… and with one special comrade with whom I shared a world, private and open.”

Leo’s voice: “There is something I need to tell you: I loved her. But it was not special in that sense – I loved her in the way that you have loved and wanted to love and be loved … And it was special in the way that simple things are special and new… which means that though the real child was a stranger to me (she talked little of her childhood), I knew that she was always aware of that special fold in the corner of each eye, a fold examined often in the mirrors of childhood, a symbol of her Indian past” …

“Peggy, the child of Texas dust and Los Angeles concrete and palms.” We see Peggy as a child, on a train. Peggy’s face, sipping from a glass, talking on the telephone, a woman in ordinary life. We see a collage of Peggy as a child.

Where Is The Past?

Now we hear Peggy’s voice: “Where is the past? … The child I was, was there … seeing into the faces of grown-ups, feeling nuances, anxieties, sensing something from the shape of the shoulders … I knew there were people who did not see… there were poor people and rich ones; for the rich ones what happened to others did not matter, a child wearing a sack was simply that kind of child; a mom with staring eyes and gaunt cheeks was simply that kind of mom.”

Images. We see poverty and depression; photos of the Dust Bowl; a young man with a sign: “Want a job, not charity, who will help me?”

Afterward, the child Peggy was, became the activist she was: Shoot Film, Not People. In her husband Leo Hurwitz’s film remembrance, we see photos of Peggy as a child in different poses and settings. The first is of Peggy as a small girl on a train going somewhere – perhaps to the adult woman she became with her sign of protest against murder, against disregard for the humanity of others; against hate.

The Child I Was

“The child I was is in me.” Images. A sliver of a moon; a boy sleeping; a baby moving its legs; lights at night in New York City. The sun rises over the water. A boy’s sleeping face begins to change. One eye opens and closes again. The child Peggy was, did not close her eyes. She kept her eyes open.

Leo’s voice: “Passerby … don’t go away. If you stay, if you allow your eyes to caress, then you will live into the tree … thus life once dead transforms itself into life again… the essence of a person has lived itself into me … this film approaches with love and anger a portion of the world she is part of and is part of her; a world whose bonds are forged either from empathy or from art, from oppression, or love…”

Peggy’s voice: “What are the hidden forces that move into open murder again and again and still unseen … (It was) felt by the child … the child somehow became a filmmaker. I saw films that made me want to make films … some films that translated themselves back to my childhood connected me to inner meanings. One of them was Native Land.” She saw it when she was twenty. What took place in Native Land happened when Peggy was nine.

Speaking Through Film

Native Land is Leo’s film. Murder, a part of it. Images. Two sharecroppers, one white one black, run from deputized men who broke up their union meeting and are now shooting. Both men are killed in cold blood on a deserted road in the backcountry where they tried to make a meager living. Paul Robeson’s voice narrates: “The south in July. Cotton country … two men dead on a road in Arkansas.”

Later, their mutual interest in showing the world, unseen, with its destructive forces brought Leo and Peggy together. Dialogue With A Woman Departed takes us back through footage of Leo’s early films about war and hate (Native Land, Heart of Spain, Strange Victory, and The Museum and the Fury). These: the oppressive forces Peggy lived with as a child; forces she fought and protested as an adult:

“Those long years, two to eight, nine, ten, a strange world lived around me. I kept reaching back into that world of the ’30s for a long time. All my life, those years … never became the dead past … how do you grasp fascism on an ordinary day? And, how do you hold onto the known? The deep cry moves into memory. An ordinary day moves into memory.”

Remembering

Images. From The Museum And The Fury: “This too the Museum remembers …” Strange Victory: “we hit hard, fighting for four Freedoms. Remember? How it was?” Remember the forces of hate: World War II. Hiroshima. Nagasaki. Joseph McCarthy.

Peggy’s voice: “I came to know I was not alone in an alien world … Yes, I was a part of it. The struggle continues … the image is on film.” Peggy became a filmmaker. Shoot film, Not People. Images. Peggy’s face in protest: “Try to remember … try now to understand.”

Martin Luther King. Vietnam. New wars, but the wars are the same: “… if we did not leave behind what we knew, if we did not lose ourselves in the particulars of each day, we could dig out something of what was happening beneath the surface of events.”

Remember. Ask the questions Peggy asked: “What does the American government want? Whose interests do they serve? What blind alleys of death are we being led into? And … what lies have made us passive?”

Images. Shoot Film, Not People. The sad troubled face of a Vietnamese mother sitting on a street corner, child in lap. Narration from The Museum And The Fury shakes our passivity: “Endless Auschwitz. Tears for the hungry, innocent, and injured … war … maker of orphans, widow-maker … litany of pain and anger: And history seems like the echo of an angry scream …”

Simultaneously, there is a grieving for the mistakes of our history or for a love lost. Yet, neither has to end in anger. Yes, grieving, at its best, is a remembering. And, grieving, through this remembering, leads us on the path to a new door – with images.

Images Lead The Way

Peggy’s voice: “Images … the world inside me, the world outside me. The more I lived, the more I understood that what was around me was a part of me … I had my lonely child struggles in Texas, anger climbing a tree. The world was separate, frequently enemy … Later; I learned I could not be disconnected from the others. I shared feelings, needs …”

Images. A man struggling in the street, a demonstration: “We demand 30% for decent American Standard of Living … strike ‘til we win.”

Peggy’s voice: “I kept reaching back into that world of the ‘30’s. Those years never became the past. A question hovered in the air, ‘did people have the right to want something more? The right to organize and strike?” A demonstration sign from her childhood: “The Spirit of 1937.”

Leo made Native Land in 1941. Indeed, he spoke Peggy’s language. Paul Robeson’s voice narrates: “Here’s how we fought the blacklist. We won back our rights as Americans. Re-organized. Went on the march. No more fear in the streets. And, no more meetings in the dark … you can’t blacklist a whole people.”

Images: Peggy as an 8-year-old; a painting of an Indian girl, the drawing of a ram. Peggy’s face in protest, her eye – the sign of her heritage, the sign of a child trying to see: of a woman who knows. Seeing: “Images of the past living in the present. The image is on film.”

A Way To Become Human

Peggy’s voice: “There is a way to become human … layers inside me, they are there, disappear … they arise in daily visions … I visited New York City when I was twelve, taken to the World’s Fair, then whisked away again. I saw it out of the corner of my eye. A set of wonders I wanted to come back to. Later, it became my home, where I lived and worked. I grew here. Became a filmmaker. I watched its changes, shifting constantly, but forever holding its shape.” New York City is the city where Leo and Peggy met.

Images: a drawing of an Indian girl in an Eagle headdress. The Eagle: courage, freedom, sharp-sightedness, victory, never willing to accept the status quo. These qualities Leo and Peggy shared in their filmmaking, with cameras as their wings. Breaking free of grief takes the same courage and strength.

Leo’s voice: “There’s something I need to tell you. I loved her … loved her in the way you have loved and wanted to love … which means that the world strange and every day is shared, touch is shared, the inner spaces of unspoken thought and feelings are shared … I loved her in a way I wish to love and be loved again.”

A Path Through Grief

Images. Grieving. Remembering the scenes of a life together – and going through them piece by piece. Images. From Light and The City, a film Peggy and Leo made together: green lights and red lights flash. Go. Stop.

Truly. Grief can stop life. But mourning openly as Leo does through Dialogue With A Woman Departed keeps memories and love alive. “The woman I loved lives in me.” The flow of life carries on.

Images. New York City. People walking. Yet, superimposed on this everyday life are images of war. Images – of city life and dead bodies, fallen in the fields of Vietnam. Death and life, just as it is strangely juxtaposed in grief: the dead and the living.

Leo’s voice: “The war was won after you died, Peggy, by the people of Indochina, a victory long in the making. You knew its source while the war was on, while the napalm was burning bodies. You knew its source: People against the machines of war, love against anonymous engines of hate, liberty against oppression, the willingness to face death, to live … We are of the same chain of love … Peggy, you, I … we are linked in the same struggle, the sons and daughters of joy.”

Shoot Film, Not People

Shoot Film, Not People. Peggy and Leo faced war and protested with their film images. And, Leo faced Peggy’s death. Neither backed down from the seemingly impossible.

Leo’s voice: “You are a shadow, an echo, the reality of a photograph; the past dies into the present … and where is your life? In the things and people you touched with hand and eye, in the essences imprinted on the now.”

Loss can seem impossible. Yet, as Leo Hurwitz’s Dialogue With A Woman Departed reminds us: “… some have hope.”

Remembering, through his beautiful and compelling film, keeps both the woman he loved – and hope – alive: “Peggy that was, was. Peggy that is, is in me, is in the suns we photographed in Vermont, Maine… is in the pictures that were only faintly you while you lived, but now are a curious arc of sensitivity and self, moving, growing to the woman you became. The image is on film.” Remembering and grieving, as Leo did, opens the door to loving, and being loved, again.